November 1958.

Sunday, 26 December 2021

Teen magazines

Monday, 4 October 2021

Sue Thompson (1925-2021) of 'Sad movies (Make me cry)' & 'Norman'

Sue Thompson, who after more than a decade of moderate sucess as a country singer found pop stardom in the early 1960s with hook-laden novelty hits like 'Sad movies (Make me cry)' and 'Norman', died on Thursday, 23rd September 2021, at the home of her daughter and care-giver Julie Jennings, in Pahrump, Nevada. She was 96. Her son, Greg Penny, said the cause was complications of Alzheimer's disease.

With a clear, somewhat girlish voice that brought sass to humorous ditties but that could also be used to good effect , Ms Thompson was part of a wave of female vocalists, like Connie Francis and Brenda Lee, who had hits in the late 50s and early 60s.

Her breakthrough came when she was paired with the songwriter John D.Loudermilk, who wrote her first big hit, 'Sad movies', a done-me-wrong tune about a woman who goes to a movie alone when her boyfriend says he has to work late, only to see him walk in with her best friend on his arms.

'Sad movies (Make me cry') got to # 5 at Billboard's Hot 100 on 23rd October 1961. Four months later, with another Loudermilk song 'Norman', in which she turned that rather unglamorous male name into an earworm ('Norman, Norman my love', Ms Thompson cooed in the chorus, surrounding the name with ooh and hmms) went even higher getting to # 3, on 24 February 1962.

Thompson never made the Top 10 again. Her follow-up to 'Norman' was a ballad, 'Have a good time', a song, by Boudleaux and Felice Bryant, Tony Bennett recorded a decade earlier. It reached # 30 on 21st July 1962. Before 1962 was over, Mr Loudermilk wrote an elopement novelty, 'James (Hold the ladder steady)' which got to # 17 on 20 October 1962.

The 1964 British Invasion soon eclipsed this kind of light fare, but Ms. Thompson had one more pop success with Mr. Loudermilk’s “Paper Tiger” which got to # 23 on 6 February 1965.

In 1966 she traveled to Vietnam to entertain the troops. Because she was accompanied by only a trio, she could go to more remote bases than bigger U.S.O. acts, exposing her to greater danger.

“Tonight we are at Can Tho, a huge American air base,” she wrote to her parents. “You can see the fighting (flashes from guns), hear the mortars, etc.” “We’re fairly secure most of the time,” she continued, “but must be aware that things can pop right in our midst.” The trip left her shaken. “A heartbreaking — and heartwarming — experience,” she wrote. “I will never be the same. I saw and learned unbelievable things.”

Mr. Penny said that his mother was ill for weeks afterward, and that she long suspected that she had been exposed to Agent Orange. She underwent a sort of awakening, he said, becoming a vegetarian and developing an interest in spiritual traditions, Eastern as well as Western.

Despite becoming ill after the first trip, she went on other tours to entertain troops, including one in 1967, the next year, on which Mr. Penny, just a boy, accompanied her. They traveled to Japan, Hong Kong, the Philippines and elsewhere. Vietnam had also been on the itinerary, but that part of the trip never happened. “I remember getting the communication while we were on the road in Okinawa,” Mr. Penny said in a phone interview. “They said it was just too dangerous.”

When Ms. Thompson returned to performing stateside, she also returned to country music, releasing a number of records — including a string recorded with Don Gibson — and leaving behind the little-girl sound of her hits.

“I don’t want to be ‘itty bitty’ anymore,” she told The Times of San Mateo, Calif., in 1974, when she was already 49. “I want to project love and convey a more mature sound and a more meaningful message.” Country music, she said, was a better vehicle for that because “country fans pay more attention to what is being said in a song.”

Eva Sue McKee (she picked her stage name out of a phone book) was born on 19 July 1925, in Nevada, Mo. Her father, Vurl, was a labourer, and her mother, Pearl Ova (Fields) McKee, was a nurse. In 1937, during the Depression, her parents moved to California to escape the Dust Bowl, settling north of Sacramento. When she was in high school the family moved again, to San Jose.

As a child Ms. Thompson was entranced by Gene Autry, and she grew up envisioning herself as a singing cowgirl. Her mother found her a secondhand guitar for her seventh birthday, and she performed at every opportunity as she went through high school.

In 1944 she married Tom Gamboa, and while he fought in World War II, she had their daughter, Ms. Jennings. She also worked in a defense factory, Mr. Penny said.

Her wartime marriage ended in divorce in 1947, but her singing career soon began in earnest. Ms. Thompson won a talent show at a San Jose theater, which led to appearances on local radio and television programs, including those of Dude Martin, a radio star in the Bay Area who had a Western swing band, Dude Martin’s Roundup Gang.

In the early 1950s she became the lead vocalist on a TV show that Mr. Martin had introduced in the Los Angeles market, and she cut several records with his band, including, in 1952, one of the first versions of the ballad “You belong to me.” Later that year it became a hit for Jo Stafford, and in the 1960s it was covered by the Duprees.

Ms. Thompson and Mr. Martin married in December 1952, but they divorced a year later, and Ms. Thompson soon married another Western swing star with his own local TV show, Hank Penny. That marriage ended in divorce in 1963, but the two continued to perform together occasionally for decades.

The country records Ms. Thompson made on the Mercury label in the 1950s never gained much traction, but that changed when she signed with Hickory early in 1961. “Angel, Angel,” another ballad by the Bryants, garnered some attention — Billboard compared it to the Brenda Lee hit “I Want to Be Wanted” — and then came “Sad Movies.”

That breakthrough hit was something of an accident. In a 2010 interview on the South Australian radio show “The Doo Wop Corner,” Ms. Thompson said she recorded it only after another singer had decided not to. “I inherited the song,” she said, “and I was really happy and excited when it turned out to be such a hit for me.”

Even before her pop hits Ms. Thompson was a familiar sight on stages in Nashville and Nevada as well as on the country fair circuit, and the hits made her even more in demand in Las Vegas, Lake Tahoe, Reno, Nev., and elsewhere.

Gravitating between country and pop came easily. “Most popular songs actually are country-and-western songs with a modern instrumental background,” she told The Reno Gazette-Journal in 1963.

Ms. Thompson said her favorite among the songs she recorded was “You belong to me.” About a decade ago, when she was in her 80s, Greg Penny, a record producer who has worked with Elton John and other top stars, recorded her singing the song to a guitar accompaniment. Carmen Kaye, host of “The Doo Wop Corner,” gave the demo its radio premiere during the 2010 interview, Ms.Thompson still sounding sweet and clear.

Her fourth husband, Ted Serna, whom she had known in high school and married in 1993, died in 2013. In addition to Ms. Jennings and Mr. Penny, she is survived by eight grandchildren and 12 great-grandchildren.

Ms. Jennings, in a phone interview, told about a time when her mother, on tour in Vietnam, asked to visit soldiers in the infirmary who couldn’t come to her stage show. One badly injured young man, when introduced to her, said, “I don’t give a darn who’s here; I just want my mama.” Ms. Thompson sat with him for a long while, asking all about his mother, helping him conjure good memories.

“Three years later,” Ms. Jennings said, “my mother was working in Hawaii, and he brought his mother in there and introduced her to my mom.”

Monday, 23 August 2021

Don Everly (1937-2021) of Everly Brothers dies at 84

Nashville, Tennessee - Don Everly, the elder of the two Everly Brothers, the groundbreaking duo whose fusion of Appalachian harmonies and a tighter, cleaner version of big-beat rock ’n’ roll made them harbingers of both folk-rock and country-rock, died on Saturday, 21st August 2021, at his home here. He was 84.

A family spokesman confirmed the death to The Los Angeles Times. No cause was given.

The most successful rock ’n’ roll act to emerge from Nashville in the 1950s, Mr. Everly and his brother, Phil, who died in 2014, once rivaled Elvis Presley and Pat Boone for airplay, placing an average of one single in the pop Top 10 every four months from 1957 to 1961.

On the strength of ardent two-minute teenage dramas like “Wake up Little Susie” and “Cathy’s Clown,” the duo all but single-handedly redefined what, stylistically and thematically, qualified as commercially viable music for the Nashville of their day. In the process they influenced generations of hitmakers, from British Invasion bands like the Beatles and the Hollies to the folk-rock duo Simon and Garfunkel and the Southern California country-rock band the Eagles.

In 1975 Linda Ronstadt had a Top 10 pop single with a declamatory version of the Everlys’ 1960 hit “When will I be loved.” Alternative-country forebears like Gram Parsons and Emmylou Harris were likewise among the scores of popular musicians inspired by the duo’s enthralling mix of country and rhythm and blues.

Paul Simon, in an email interview with The Times the morning after Phil Everly’s death, wrote: “Phil and Don were the most beautiful sounding duo I ever heard. Both voices pristine and soulful. The Everlys were there at the crossroads of country and R&B. They witnessed and were part of the birth of rock 'n' roll.”

“Bye Bye Love,” with its tight harmonies, bluesy overtones and twanging rockabilly guitar, epitomized the brothers’ crossover approach, spending four weeks at No. 2 on the Billboard pop chart in 1957. It also reached the top spot on the country chart and the fifth spot on the R&B chart.

Art Garfunkel and Don Everly performed in Hyde Park, London, in 2004. Mr. Everly recorded several solo albums.

As with many of their early recordings, including the No. 1 pop hits “Bird dog” and “All I have to do is dream,” “Bye bye love” was written by the husband-and-wife team of Felice and Boudleaux Bryant and featured backing from Nashville’s finest session musicians.

Both brothers played acoustic guitar, with Don being regarded as a rhythmic innovator, but it was their intimate vocal blend that gave their records a distinctive and enduring quality. Don, who had the lower of the two voices, typically sang lead, with Phil singing a slightly higher but uncommonly close harmony part.

“It’s almost like we could read each other’s minds when we sang,” Mr. Everly told The Los Angeles Times shortly after his brother’s death.

The warmth of their vocals notwithstanding, the brothers’ relationship grew increasingly fraught as their career progressed. Their radio hits became scarcer as the ’60s wore on, and both men struggled with addiction. Don was hospitalized after taking an overdose of sleeping pills while the pair were on tour in Europe in 1962.

A decade later, after nearly 20 years on the road together, their longstanding tensions came to a head. Phil smashed his guitar and stormed offstage during a performance at Knott’s Berry Farm in Buena Park, Calif., in 1973, leaving Don to finish the set and announce the duo’s breakup.

“The Everly Brothers died 10 years ago,” he told the audience, marking the end of an era.

Isaac Donald Everly was born on 1st February 1937, in Brownie, Ky., not quite two years before his brother. Their mother, Margaret, and their father, Ike, a former coal miner, performed country music throughout the South and the Midwest before moving the family to Shenandoah, Iowa, in 1944. Shortly after their arrival there, “Little Donnie” and “Baby Boy Phil,” then ages 8 and 6, made their professional debut on a local radio station, KMA.

The family went on to perform on radio in Indiana and Tennessee before settling in Nashville in 1955, when the Everly brothers, now in their teens, were hired as songwriters by the publishing company Acuff-Rose. Two years later Wesley Rose of Acuff-Rose would help them secure a recording contract with Cadence Records, an independent label in New York, with which they had their initial success as artists.

Phil and Don Everly at the 10th annual Everly Brothers Homecoming concert in Central City, Ky., in 1997. The brothers had a fraught relationship and the act broke up in 1973, but they later reunited.

Phil and Don Everly at the 10th annual Everly Brothers Homecoming concert in Central City, Ky., in 1997. The brothers had a fraught relationship and the act broke up in 1973, but they later reunited.Credit...Suzanne Feliciano/Messenger-Inquirer, via Associated Press

Don’s first break as a writer came with “Thou Shalt Not Steal,” a Top 20 country hit for Kitty Wells in 1954, as well as with songs recorded by Anita Carter and Justin Tubb. He also wrote, among other Everly Brothers hits, “(’Til) I Kissed You,” which reached the pop Top 10 in 1959, and “So Sad (To Watch Good Love Go Bad),” which did the same the next year. “Cathy’s Clown,” which he wrote with Phil, spent five weeks at the top of the pop chart in 1960.

That record was the pair’s first hit for Warner Bros., which signed them after they left Cadence over a dispute about royalty payments in 1960. They moved from Nashville to Southern California the next year.

Their subsequent lack of success in the United States — they continued to do well in England — could be attributed to any of a number of factors: the brothers’ simultaneous enlistment in the Marine Corps Reserve in 1961; their lack of access to material from the Bryants after their split with Cadence and Acuff-Rose; the meteoric rise of the Beatles, even though their harmonies on breakthrough hits like “Please Please Me” were modeled directly on those of the Everlys.

They nevertheless continued to tour and record, releasing a series of influential albums for Warner Bros., notably “Roots,” a concept album that reckoned with the duo’s legacy and caught them up with the country-rock movement to which they gave shape.

Don also released a self-titled album on the Ode label in 1970 and made two more solo albums, “Sunset Towers” on Ode and “Brother Juke Box” on Hickory, after the Everlys split up.

In 1983 he and his brother reunited for a concert at the Royal Albert Hall in London, a show that was filmed for a documentary. The next year they recorded “EB84,” a studio album produced by the Welsh singer-guitarist Dave Edmunds. That project included the minor hit “On the Wings of a Nightingale,” written for the Everlys by Paul McCartney.

The duo released two more studio albums before the end of the decade. They were inducted as members of the inaugural class of the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 1986.

They also received a Grammy Award for lifetime achievement in 1997 and were enshrined in the Country Music Hall of Fame in 2001.

In 2003 they toured with Simon and Garfunkel, and in 2010 they appeared on an album by Don’s son, Edan Everly.

In an interview with The Los Angeles Times in 2014, Mr. Everly acknowledged his decades of conflict with his brother but recalled their intimate musical communion with pride.

“When Phil and I hit that one spot where I call it ‘The Everly Brothers,’” he said, “I don’t know where it is, ’cause it’s not me and it’s not him; it’s the two of us together.”

Tuesday, 27 July 2021

Laura Nyro (1947-1997)

Laura Nyro: the phenomenal singers’ singer the 60s overlooked

Elton John idolised her and she wrote hits for the likes of Barbra Streisand, but her musical ambitions were out of sync with the times. Now a new collection reveals her intense originality in full

by Richard Williams for The Guardian

Tuesday, 27 July 2021

Whatever role Laura Nyro chose to play – earth mother, soul sister, angel of the Bronx subways – she committed to it. With a soaring, open-hearted voice and ingeniously crafted compositions, Nyro transformed a range of influences into her own kind of art song. She made vertiginous shifts from hushed reveries to ecstatic gospel-driven shout-ups with an intensity and a courage that, as Elton John would point out, left its mark on many contemporaries who achieved greater commercial success.

As the music of the 1960s reached a climax, no one else merged the new songwriting freedoms pioneered by Bob Dylan with the pop sensibility of the Brill Building tunesmiths to such intriguing effect. As a teenager, she wrote "And when I die" and "Stoney End", songs that became hits for Blood Sweat & Tears and Barbra Streisand. Her own enigmatically titled albums – "Eli and the Thirteenth Confession", "New York Tendaberry", "Christmas and the Beads of Sweat" – showed a precociously sophisticated sensibility.

Later, rejecting commercial pressures, she would help push the boundaries of popular music by writing songs celebrating motherhood, female sexuality and her menstrual cycle. In the hearts of admirers, she kindled a loyalty fierce enough to withstand the semi-obscurity into which she had fallen by the time of her death from ovarian cancer in 1997, at 49. But a new generation will this month get to hear Nyro’s music, as American Dreamer, a box set containing her first seven albums and an eighth disc of rarities and live tracks, is released.

The dimming of her fame had been gradual and, to an extent, self-actuated. If her early songs seemed to give listeners the thrill of overhearing her innermost thoughts, she lived her adult life edging towards the spotlight before withdrawing to cope with personal upheavals, then re-emerging years later with songs that confounded expectations by explicitly affirming new commitments to radical feminism, animal rights and environmental activism.

She made her anticipated UK debut at London’s Royal Festival Hall in 1971, with her then-boyfriend, Jackson Browne, as the support act. Her final visit, 23 years later, was to the Union Chapel in Islington, a more intimate affair, where she performed as if to family or friends, bathed in an outpouring of warmth. She had become the property of true believers, a following that expanded again as new generations discovered her inspiring originality.

Laurel Canyon hippy chic was never her costume. She was a New Yorker, with Broadway in her soul

Early admirers had included not only female counterparts such as Rickie Lee Jones and Suzanne Vega but also Todd Rundgren (“I stopped writing songs like the Who and started writing songs like Laura Nyro”) and Elton John (“I idolised her. The soul, the passion, the out-and-out audacity … like nothing I’d ever heard before”). But to the music industry, there was the enduring problem of who, or what, she really was and where she belonged.

In the late 1960s, helped by a partnership with the ambitious young agent David Geffen, who became her manager, she was one of a handful of rising singer-songwriters. But Laurel Canyon hippy chic was never her costume. She had not emerged from the folk or rock traditions. She was a New Yorker, with Broadway and the Brill Building in her soul. Even when Browne was her boyfriend, part of her belonged to a different, pre-Beatles world.

That dissonance was apparent in her much-discussed appearance alongside the likes of the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane at the 1967 Monterey pop festival, a landmark event for the emerging counterculture. Jimi Hendrix set fire to his guitar and the Who destroyed their stage equipment, with career-defining impact in both cases. The mohair-suited Otis Redding, seemingly out of place, captivated what he called “the love crowd”. Janis Joplin so impressed Clive Davis, the president of Columbia Records, that she and her band, Big Brother and the Holding Company, were signed on the spot.

Nyro had made an effort. She took the stage in a sleeveless black gown, clutching the microphone with pale fingers that ended in long red-painted nails. She brought with her two female backing singers in matching dresses and a well-rehearsed band consisting of top Hollywood session men. The decision not to accompany herself on the piano robbed her of a certain credibility with this audience, and her songs sometimes seemed to be addressed elsewhere. “Kisses and love won’t carry me / ‘Til you marry me, Bill” – from "Wedding Bell Blues" – was a take on romance the audience associated with their parents’ generation.

Although some found her performance overwrought and uncomfortable, she was not booed off as legend has it. Footage shot by the documentary film-maker D.A. Pennebaker shows that she was being listened to as she drew out the a cappella delivery of Poverty Train’s climax for maximum effect: “Getting off on sweet cocaine / It feels so good …” But the underlying vibe was wrong, and she was spooked.

It didn’t help that when other people had hits with her songs, they were the wrong people. The Fifth Dimension ('Wedding Bell Blues') were a supper-club soul act of the highest class. Barbra Streisand ('Stoney End') was Broadway royalty, Three Dog Night ('Eli's coming'). Blood, Sweat & Tears had shaken off all traces of their Greenwich Village origins by the time they recorded "And when I die". In the public mind, their superficial showbiz gloss transferred to the writer. Nevertheless, shortly after Monterey, Clive Davis also signed her following a private audition in which he was impressed by her conviction.

The songs she wrote for her Columbia albums continued to mine deeper feelings. She cast a golden glow on female friendship in the exquisite "Emmie" and stripped away all ornamentation to sing about addiction in "Been on a train". Sometimes she luxuriated in the exotic: “Where is your woman? Gone to Spanish Harlem, gone to buy you pastels, gone to buy you books.”

In 1971, the year of Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On, she sang: “I love my country as it dies / In war and pain before my eyes.” Great musicians contributing to her albums included the harpist Alice Coltrane, the saxophonist Zoot Sims and the bassist Richard Davis, who had played on Eric Dolphy’s Out to Lunch! and Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks.

“Where did it come from?” Bette Midler would ask, wiping away real tears while inducting Nyro into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame 15 years after her death. Her Italian-Ukrainian father, Lou Nigro, was a trumpeter in big bands; an uncle on her mother’s side was a cantor; on the record player at home there would be jazz, Broadway musicals, opera, folk songs and symphonies.

As she grew, she listened to the doo-wop groups whose songs she and her school friends practised in the subways. Miles Davis and John Coltrane were among her musical heroes. From 14 to 17, she attended the High School of Music and Art in Harlem, studying classical singing and counterpoint while looking, in the words of a friend quoted in Michele Kort’s excellent 2002 biography, "Soul Picnic", “very much like a beatnik”. Her graduation ceremony, in the summer of 1965, was held at Carnegie Hall, on a stage from which she would one day give concerts under the name she adopted (and pronounced “Nero”) as soon as she started writing and performing professionally.

But in 1971, without a hit of her own from four albums of original songs, she decided to make an album of covers reflecting her roots, sourced from Motown, doo-wop and uptown soul, with harmonies supplied by her friends Patti LaBelle, Nona Hendryx and Sarah Dash, collectively known as Labelle. Two years before David Bowie’s Pin-Ups and Bryan Ferry’s These Foolish Things, Nyro’s exhilarating "Gonna Take a Miracle" proved to be ahead of its time.

Dismayed by its commercial failure and the acrimonious end of her close relationship with Geffen, she took initial comfort from a marriage to David Bianchini, a handsome young college drop-out who had served in Vietnam and worked sporadically as a carpenter. They moved to a house in Danbury, Connecticut and she disappeared from view.

By the time she re-emerged in 1975, promoting a new album titled "Smile", the marriage was over. Three years later another album, "Nested", coincided with the birth of a son, Gil, to whom she gave her ex-husband’s surname even though the child was conceived during a brief relationship with another man. Her albums – the next, in 1984, was called "Mother’s Spiritual" – reflected new concerns. A 17-year relationship with Maria Desiderio, a Danbury bookseller, was celebrated in songs that brought her a new audience.

“I was a foolish girl but now I’m a woman of the world,” she sang in 1993 on a track from "Walk the Dog and Light the Light", the last studio album released during her lifetime. The contours of her new songs were less startling and there were fewer verbal starbursts. But on tour, usually with two or three other women providing harmonies, she mixed the songs of her youth with those of her maturity in a way that left no doubt who this extraordinary artist really was.

A beginner’s guide to Laura Nyro

'Eli and the Thirteenth Confession' (1968)

After a somewhat conservative debut album, her second effort – abetted by arranger and co-producer Charlie Calello – was an unstoppable display of musical and verbal fireworks, exploring the emotional extremes.

'New York Tendaberry' (1969)

To the hardcore fan, her masterpiece. The mood is darker, the arrangements more minimalist, highlighting the sense of desperation fuelling a soul-baring urban song-cycle. The finest distillation of her allure.

'Gonna Take a Miracle' (1971)

After four albums of original material, she and Labelle settled into Philadelphia’s Sigma Sound to record a joyful series of cover versions. Just hear how they turn the Originals’ The Bells into a soaring aria.

'Walk the Dog and Light the Light' (1993)

More measured in its maturity but still filled with spirit and urgency, the last studio album released during her lifetime reflects her new range of feminist and ecological concerns.

'The Loom’s Desire' (2002)

Recorded in front of adoring audiences at New York’s Bitter End in 1993-94, with a harmony trio providing support, this double set captures the warmth and intimacy of her final performances.

American Dreamer is released by Madfish on 30 July 2021.

This article was amended on 27 July 2021 because an earlier version referred to Danbury, Massachusetts, whereas it is in Connecticut.

Monday, 7 June 2021

B.J. Thomas (1942-2021)

B.J. Thomas, ‘Raindrops keep fallin’ on my head’ singer, dies at 78

By Bill Friskics-Warren

30 May 2021

B.J. Thomas, a country and pop hitmaker and five-time Grammy winner who contributed to the Southernization of popular music in the 1960s and 1970s, died on Saturday, 29 May 2021, at his home in Arlington, Texas. He was 78.

The cause was complications of lung cancer, said a spokesman, Jeremy Westby of 2911 Media.

Mr. Thomas’s biggest hit was “Raindrops keep fallin’ on my head,” which was originally featured in the 1969 movie “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” and spent 4 weeks at # 1 of the pop chart in early 1970; 3rd January 1970 to 24 January 1970.

Written and produced by Burt Bacharach and Hal David, “Raindrops” — a cheery ditty about surmounting life’s obstacles — won the Academy Award for best original song later that year. Mr. Thomas’s recording was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 2014.

Mr. Thomas placed 15 singles in the pop Top 40 from 1966 to 1977. “(Hey won’t you play) Another somebody done somebody wrong song,” a monument to heartache sung in a bruised, melodic baritone, reached # 1 on both the country and pop charts on 26 April 1975.

“Hooked on a feeling,” an exultant expression of newfound love from 1968, also reached # 5 (for 2 weeks) on 11 January 1969 (Augmented by an atavistic chant of “Ooga-chaka-ooga-ooga,” the song became a # 1 pop hit as recorded by the Swedish rock band Blue Swede on 6 April 1974.)

Mr. Thomas’s records helped introduce a smooth, down-home sensibility to the AM airwaves, an approach shaped by the fusion of country, gospel, rock and R&B in the music of Elvis Presley. This uniquely Southern mix of styles became common currency on radio playlists across the nation, recognizable as well in hits by singers with similarly expressive voices like Brook Benton and Conway Twitty.

“I try to give the soft pop sound a natural relaxed feeling,” Mr. Thomas said in “Home where I belong,” a memoir written with Jerry B. Jenkins. “I guess that’s why my records always cross over and are good sellers on the pop and rock charts, as well as country.”

His debt to Presley’s romantic crooning notwithstanding, Mr. Thomas cited the music of Black R&B singers like Little Richard and Jackie Wilson as his greatest vocal inspiration.

“We all loved Elvis and Hank Williams, but I think Wilson had the biggest influence on me,” he said in his memoir. “I couldn’t believe what he could do with his voice. I’ve always tried to do more with a note than just hit it, because I remembered how he could sing so high and so right, really putting something into it.”

Mr. Wilson’s stamp is evident on “Mighty clouds of joy,” a rapturous, gospel-steeped anthem that reached # 8 at the Billboard chart for Mr. Thomas on 21st August 1971. His command of musical dynamics is especially impressive on the chorus, where, lifting his voice heavenward, he goes from a hushed whisper to a flurry of ecstatic wailing before bringing his vocals back down to a murmur for the next verse.

Mr. Thomas came by his sense of redemption the hard way. He struggled for the better part of 10 years with a dependence on drugs and alcohol that almost destroyed his marriage and his life. After getting clean in the mid-70s, he enjoyed parallel careers as a country and gospel singer, releasing three No. 1 country singles over the ensuing decade and winning five Grammy Awards in gospel categories.

Billy Joe Thomas was born on 7 August 1942, in Hugo, Okla., the second of three children of Vernon and Geneva Thomas. He was raised in Rosenberg, Texas, some 40 miles southwest of Houston. The family was poor, a condition exacerbated by his father’s violent temper and drinking. As an adolescent, B.J. (as he had come to be called playing Little League baseball) sang in the Baptist church his family attended.

While in high school he and his older brother, Jerry, joined a local pop combo, the Triumphs, with Mr. Thomas singing lead. In 1966, after three years of playing at dances and American Legion halls, the band had its first hit with a rendition of Hank Williams’s “I’m so lonesome I could cry” that reached # 8 on 9 April 1966. 'Mama' reached # 22 on 18 June 1966.

Credited to B.J. Thomas & the Triumphs and issued on the small Pacemaker label, the record was eventually picked up for distribution by the New York-based Scepter Records, home to major pop artists of the day like Dionne Warwick and the Shirelles. With sales of more than a million copies, it secured Mr. Thomas a place on the bill of a traveling rock ’n’ roll revue hosted by Dick Clark, the “American Bandstand” host and producer.

Despite the persistence and severity of his alcohol and drug use, Mr. Thomas’s recordings remained a constant on the pop chart for the next decade. 'I just can't help believing' was # 9 on 22nd August 1970; 'Oh me oh my' never charted in the USA but it reached # 2 in Brazil, on 11 September 1971.

'Long ago tomorrow' only managed to hit # 61 on 18 December 1971, but “Rock and roll lullaby,” reached # 15 on 1st April 1972, featuring Duane Eddy on guitar and backing vocals from Darlene Love and The Blossoms. Three years earlier, Mr. Thomas had enjoyed an extended run at the Copacabana in New York, brought about by the runaway success of “Hooked on a feeling.”

He started on the path to recovery after converting to Christianity in the mid-70s, a period in which he also reconciled with his wife, Gloria, after repeated separations. In 1977, following a year or so in recovery, he sang at the memorial service for Presley, whose death that year had largely been attributed to his excessive use of prescription medications.

Mr. Thomas continued to make albums and tour into the 2000s. 'Whatever happened to old fashioned love songs?' was Billboard's # 93 on 21st May 1983, but played a lot on the Australian airwaves Over the years he also sang and testified at the evangelical crusades of Billy Graham and other large religious gatherings.

He is survived by Gloria Richardson Thomas, his wife of 53 years; three daughters, Paige Thomas, Nora Cloud and Erin Moore; and four grandchildren.

At its smoothest and most over-the-top, Mr. Thomas’s music could border on schmaltz. But at its most transcendent, as on the stirring likes of “Mighty clouds of joy,” he inhabited the junction of spirituality and sentiment with imagination and aplomb, making records that had many listeners singing along.

“The greatest compliment a person could pay my music is to listen and sing along with it and think that he can sing just as good as me,” Mr. Thomas said in his memoir, alluding to the accessibility of his performances. “He probably can’t, of course, or he’d be in the business, but I want it to sound that way anyway.”

Saturday, 1 May 2021

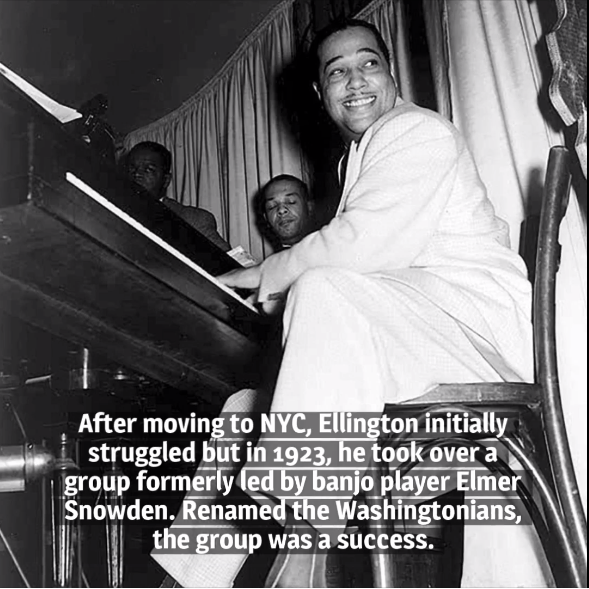

Duke Ellington

Duke Ellington may not be exactly 60s or 70s but he was everything... and besides, I'm proud to say I saw Duke Ellington in person in the early fall of 1972 (two year before he died on 24 May 1974) waiting for a cab in front of the Madison Square Garden. I saw that giant of a man trying to catch a cab and I knew instantly that he was the legendary Duke Ellington even though nodoby seemed to pay attention to him. He wore an over coat and was super elegant...

Tuesday, 16 March 2021

Sally Grossman, the girl on the cover of Bob Dylan's 'Bringing it all back home' (1965)

Sally Grossman, immortalized on a Dylan album cover, dies at 81

She picked out a red outfit and struck a relaxed pose on the cover of “Bringing it all back home,” leaving much for fans to guess about.

Bob Dylan wanted his manager’s wife, Sally Grossman, to appear on the cover of his 1965 album taken at her home in Woodstock, N.Y.

By Neil Genzlinger

15 March 2021

One of Bob Dylan’s most important early albums, “Bringing it all back home” from 1965, has the kind of cover that can strain eyes and fuel speculation. It is a photograph of Mr. Dylan, in a black jacket, sitting in a room full of bric-a-brac that may or may not mean something, staring into the camera as a woman in a red outfit lounges in the background.

“Fans became so fixated on deciphering it,” the music journalist Neil McCormick wrote in The Daily Telegraph of London last year, “that a rumor took hold that the woman was Dylan in drag, representing the feminine side of his psyche.”

She wasn’t. She was Sally Grossman, the wife of Mr. Dylan’s manager at the time, Albert Grossman.

“The photo was shot in Albert Grossman’s house,” the man who took it, Daniel Kramer, told The Guardian in 2016. “The room was the original kitchen of this house that’s a couple hundred years old.”

“Bob contributed to the picture the magazines he was reading and albums he was listening to,” Mr. Kramer added, a reference to the bric-a-brac. “Bob wanted Sally to be in the photo because, well, look at her! She chose the red outfit.”

Ms. Grossman died on Thursday, 11 February 2021, at her home in the Bearsville section of Woodstock, N.Y., not far from the house where the photograph was taken. She had long been a fixture in Woodstock, operating a recording studio, a theater and other businesses there after her husband died of a heart attack at 59 in 1986. She was 81.

Her niece, Anna Buehler, confirmed her death and said the cause had not been determined.

Ms. Grossman in an undated photo, taken in the same room, against the same fireplace, in which the 1965 album cover photo was shot. She and her husband ran recording studios and restaurants in Woodstock, and after his death she created the Bearsville Theater there.

She and her husband ran recording studios and restaurants in Woodstock, and after his death she created the Bearsville Theater there.

Sally Ann Buehler was born on 22nd August 1939, in Manhattan to Coleman and Ann (Kauth) Buehler. Her mother was executive director of the Boys Club (now the Variety Boys and Girls Club) of Queens; her father was an actuary.

Ms. Grossman studied at Adelphi University on Long Island and Hunter College in Manhattan, but she was more drawn to the arts scene percolating in Greenwich Village.

“I figured that what was happening on the street was a lot more interesting than studying 17th-century English literature,” she told Musician magazine in 1987, “so I dropped out of Hunter and began working as a waitress. I worked at the Cafe Wha?, and then the Bitter End, all over.”

Along the way she met Mr. Grossman, who was making his name managing folk music acts that played at those types of venues, including Peter, Paul & Mary, whom he helped bring together.

“The office was constantly packed with people,” Ms. Grossman recalled in the 1987 interview. “Peter, Paul and Mary, of course, but also Ian & Sylvia, Richie Havens, Gordon Lightfoot, other musicians, artists, poets.”

The couple, who married in 1964, settled in Woodstock, where Mr. Grossman had acquired properties and which Mr. Dylan had also discovered about the same time, settling there with his family as well.

In due course came the photo shoot for the album cover.

“I made 10 exposures,” Mr. Kramer told The Minneapolis Star Tribune in 2014. One image, with Mr. Dylan holding a cat, was a keeper. “That was the only time all three subjects were looking at the lens,” Mr. Kramer said.

The photo, staged by Mr. Kramer with Mr. Dylan’s input, was an early example of what became a mini-trend of loading covers up with imagery that seemed to invite scrutiny for insights into the music. The Beatles’ “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” (1967) might be the best-known example.

The album itself was a breakthrough for Mr. Dylan, marking his transition from acoustic to electric. Its tracks included “Mr. Tambourine Man,” “Subterranean homesick blues” and “Maggie’s farm.”

Ms. Grossman and her husband established recording studios and restaurants in Bearsville, and after his death Ms. Grossman renovated a barn to create the Bearsville Theater, bringing to life a vision of her husband’s. It hosted numerous concerts over the years. She sold the businesses in the mid-2000s.

Ms. Grossman is survived by a brother, Barry Buehler.

Though she knew many American musicians, Ms. Grossman had a special place in her heart for an order of religious singers from Bengal known as the Bauls, whom she encountered in the 1960s. She created a digital archive of Baul music. Deborah Baker, author of “A Blue Hand: The Beats in India” (2008), wrote about Ms. Grossman and her connection to the Bauls in a 2011 essay in the magazine the Caravan.

“Despite all the famous musicians and bands who once passed through her life,” Ms. Baker wrote, “she found it was the Bauls she missed the most from those years.”

Ms. Grossman in an undated photo, taken in the same room, against the same fireplace, in which the 1965 album cover photo was shot. She and her husband ran recording studios and restaurants in Woodstock, and after his death she created the Bearsville Theater there.

Tuesday, 2 March 2021

Alan Freed the man who created the name Rock'n'Roll

Alan Freed at the microphone of New York's WINS at the height of his popularity. Freed was born on 16 December 1921.